Happy Black History Month!

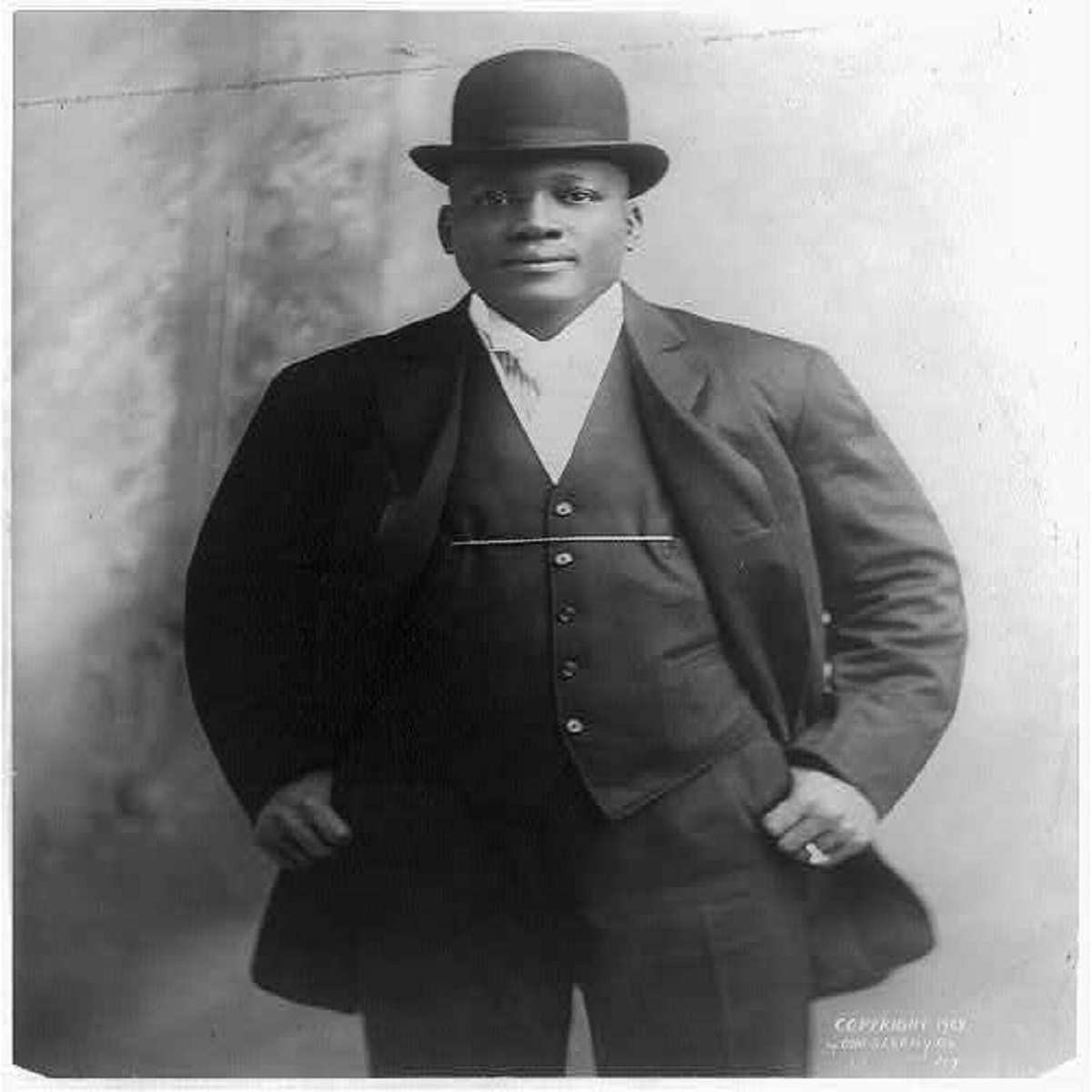

Hero of the American Revolution and Slave. James Armistead Lafayette. They Don't Teach You THIS in American History Class! He was the spy who gave America the victory in the revolution battle of Yorktown.

He Delivered Intentionally False Military Intelligence to General Cornwallis... Who BELIEVED IT... Causing the British to Lose the Battle! Thanks!https://face2faceafrica.com/article/remembering-james-armistead-the-double-spy-who-gave-america-victory-in-the-revolution-battle

https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/james-armistead-lafayette

.jpeg)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Armistead_Lafayette

Born into slavery around 1760, James Armistead lived most of his life on a plantation in New Kent, Virginia. During the American Revolution, however, James received permission from his master, William Armistead, to enlist in the Marquis de Lafayette’s French Allied units. Here, the army dispatched Armistead as a spy, playing the role of a runaway slave to gain access to General Cornwallis’s headquarters. Because Armistead was a native Virginian with extensive knowledge of the terrain, the British received him without suspicion. As a result, Armistead accomplished what few spies could: direct access to the center of the British War Department.

After successfully infiltrating British intelligence, Armistead floated freely between the British and American camps. As a double agent, he relayed critical information to Lafayette and misleading intel to the enemy. Oblivious to his true intentions, the British assigned Armistead to work under the notorious turncoat, Benedict Arnold. By helping Arnold maneuver his troops through Virginia, Armistead gained significant insight into the Redcoats’ movements.

Several of Armistead’s finest acts occurred in 1781, during a critical moment in the Revolution—the Battle of Yorktown. The spy informed Lafayette and Washington about approaching British reinforcements, which allowed the generals to devise a blockade impeding enemy advancements. This success resulted in the final major victory for the colonists when Lord Cornwallis surrendered on October 17, 1781.

Though Americans celebrated freedom throughout the United States at the end of the war, James Armistead returned to life as a slave. His status as a spy meant that he did not benefit from the Act of 1783, which emancipated any slave-soldiers that fought for the Revolution.

As a result, Armistead began the process of petitioning Congress to fight for his freedom. After several years without success, Armistead received help from an old comrade in arms, the Marquis de Lafayette. Upon learning that Armistead remained enslaved, Lafayette wrote a letter to Congress on his behalf. Armistead received his manumission in 1787.

Living off his annual pension fee, Armistead moved to his own 40-acre farm in Virginia, where he married, raised a family, and lived out the rest of his life as a freeman. Armistead added Lafayette to his name as a token of gratitude and a testament to the bond the former slave and French general shared.

The two crossed paths again during Lafayette’s grand tour of the United States in 1824, where the general picked James out of a crowd and cordially embraced him. James Armistead Lafayette died in 1832.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agent_355

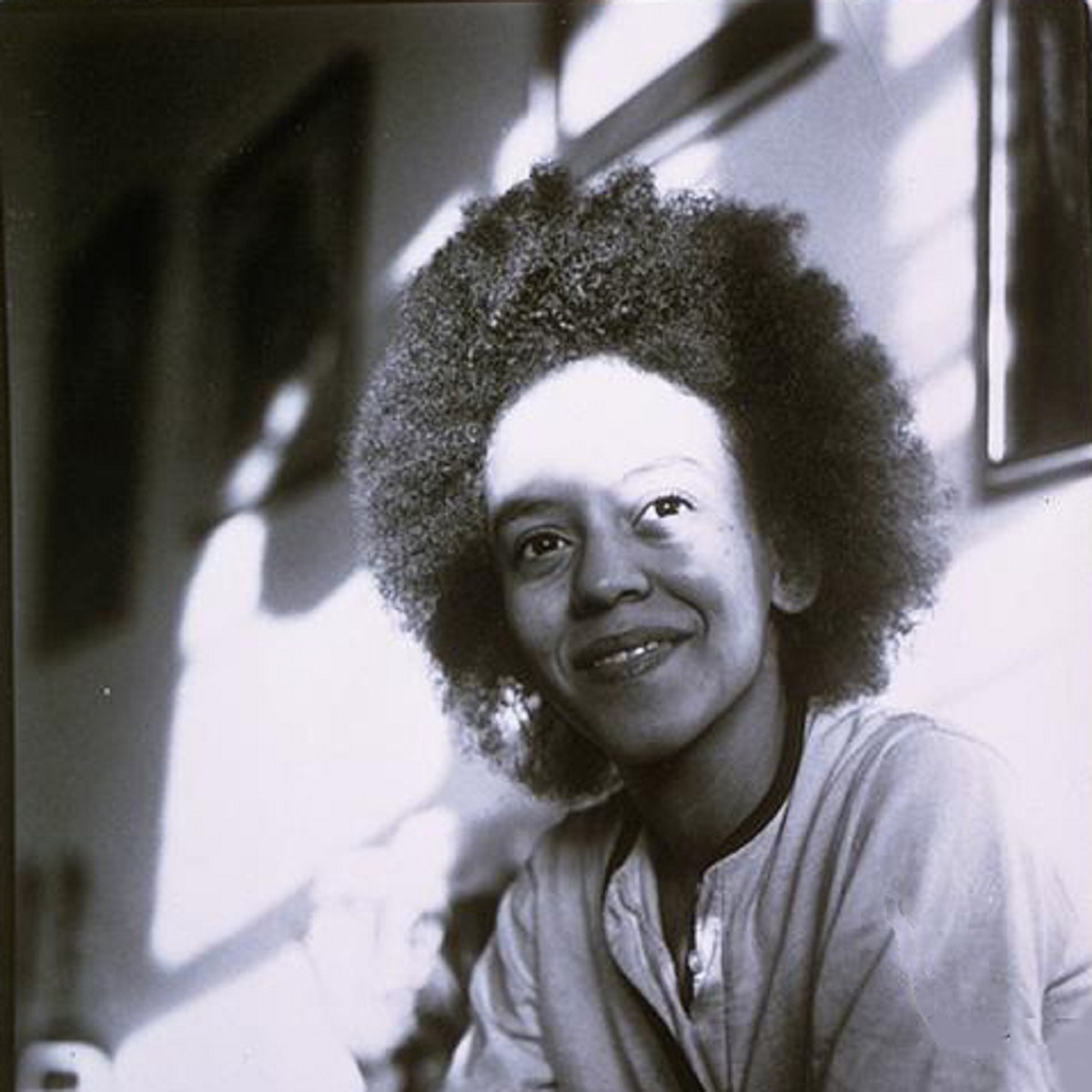

355 (died after 1780) was the code name of a female spy during the American Revolution, part of the Culper Ring. She was one of the first spies for the United States, but her real identity is unknown.[1] The number 355 could be decrypted from the system the Culper Ring used to mean "lady."[2]

Biography:

The only direct reference to 355 in any of the Culper Ring's missives (1778–1780)[3] appears in a letter from Abraham Woodhull ("Samuel Culper Sr.") to General George Washington,[4] where Woodhull describes her as "one who hath been ever serviceable to this correspondence."[5]

The true identity of 355 remains unknown, but some facts about her seem clear. She worked with the American Patriots during the Revolutionary War as a spy, and was likely recruited by Woodhull into the spy ring.[1] The way the code is constructed indicates that she may have had "some degree of social prominence."[2] She was likely living in New York City at the time,[6] and at some point had contact with Major John André and Benedict Arnold.[7][8] One person who has been named as the possible identity of Agent 355 was Anna Strong, Woodhull's neighbor.[6] Strong allegedly helped the Culper Ring by signaling to its members the location of Caleb Brewster, who raided British shipments in his whaleboat around Long Island Sound after he was given a secure location by Strong.[3]

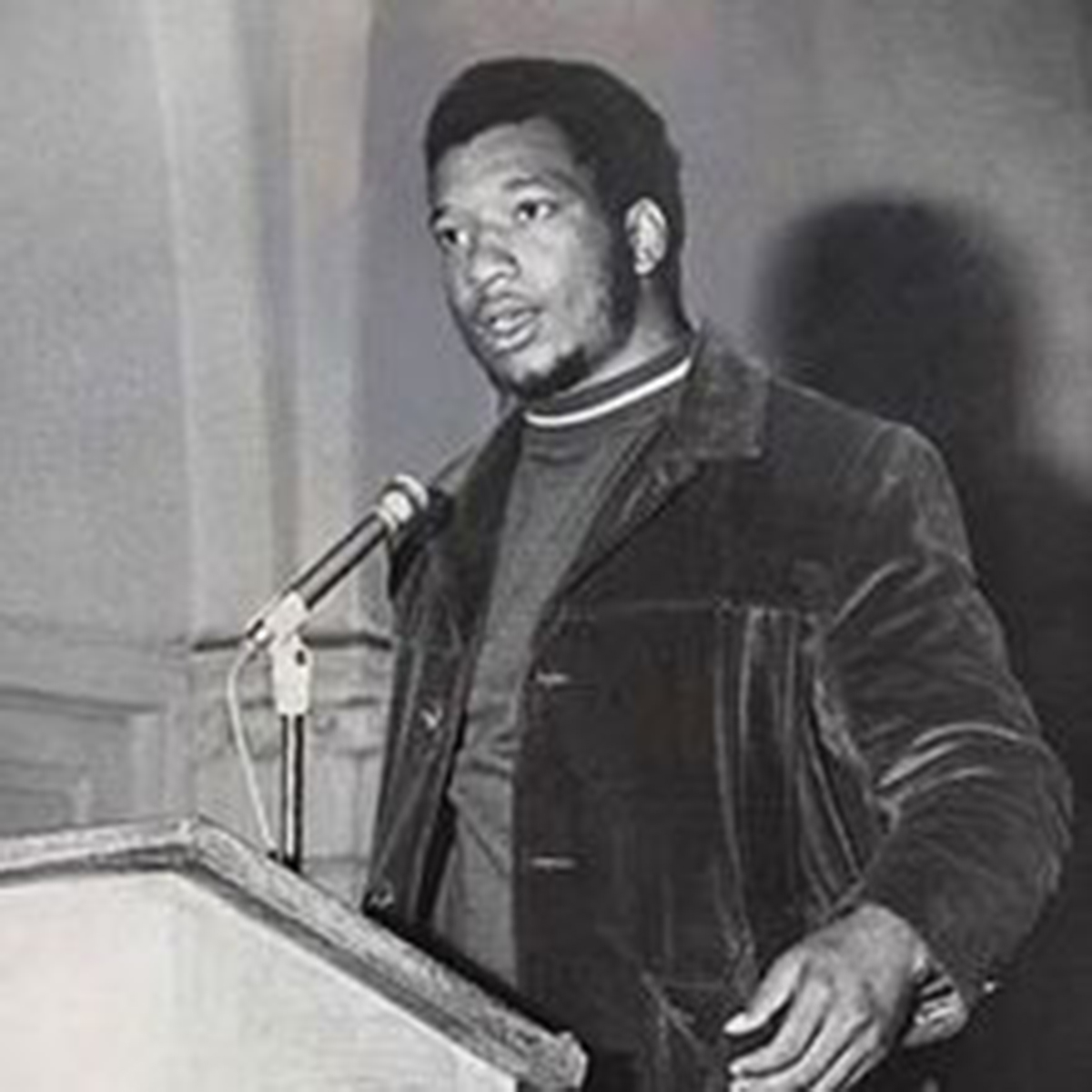

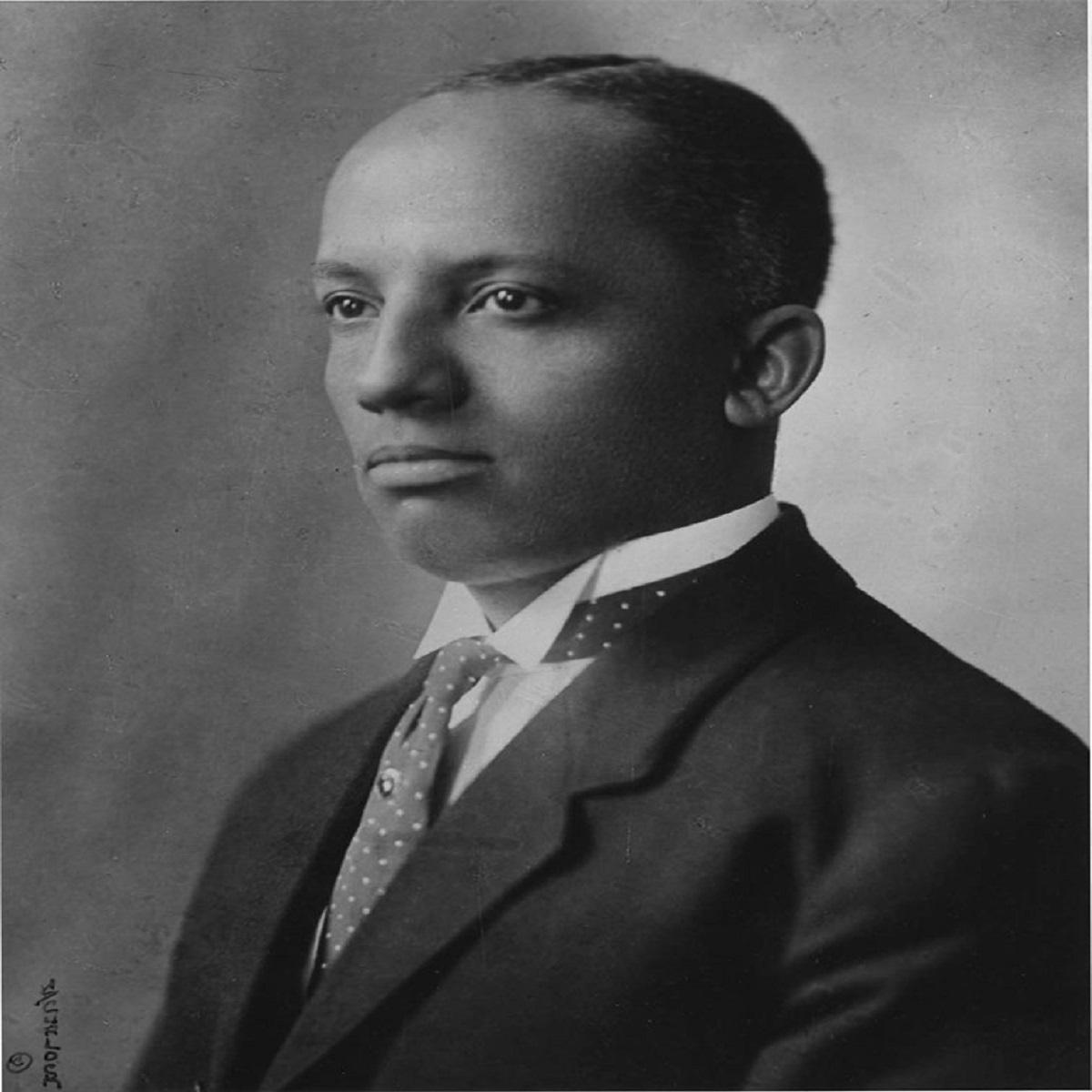

This day in history 1942: George Washington Carver begins experimental project with Henry Ford.

The agricultural chemist George Washington Carver, head of Alabama’s famed Tuskegee Institute, arrives in Dearborn, Michigan at the invitation of Henry Ford, founder of Ford Motor Company.

Born to slave parents in Missouri during the Civil War, Carver managed to get a high school education while working as a farmhand in Kansas in his late 20s.

Turned away by a Kansas university because he was an African American, Carver later became the first black student at Iowa State Agricultural College in Ames, where he obtained his bachelor’s and master’s degrees. In 1896, Carver left Iowa to head the department of agriculture at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute, a school founded by the leading black educator Booker T. Washington. By convincing farmers in the South to plant peanuts as an alternative to cotton, Carver helped resuscitate the region’s agriculture; in the process, he became one of the most respected and influential scientists in the country.

Like Carver, Ford was deeply interested in the regenerative properties of soil and the potential of alternative crops such as peanuts and soybeans to produce plastics, paint, fuel and other products. Ford had long believed that the world would eventually need a substitute for gasoline and supported the production of ethanol (or grain alcohol) as an alternative fuel. In 1942, he would showcase a car with a lightweight plastic body made from soybeans. Ford and Carver began corresponding via letter in 1934, and their mutual admiration deepened after Carver made a visit to Michigan in 1937.

As Douglas Brinkley writes in “Wheels for the World,” his history of Ford, the automaker donated generously to the Tuskegee Institute, helping finance Carver’s experiments, and Carver in turn spent a period of time helping to oversee crops at the Ford plantation in Ways, Georgia.

By the time World War II began, Ford had made repeated journeys to Tuskegee to convince Carver to come to Dearborn and help him develop a synthetic rubber to help compensate for wartime rubber shortages. Carver arrived on July 19, 1942, and set up a laboratory in an old water works building in Dearborn. He and Ford experimented with different crops, including sweet potatoes and dandelions, eventually devising a way to make the rubber substitute from goldenrod, a plant weed.

Carver died in January 1943, Ford in April 1947, but the relationship between their two institutions continued to flourish.

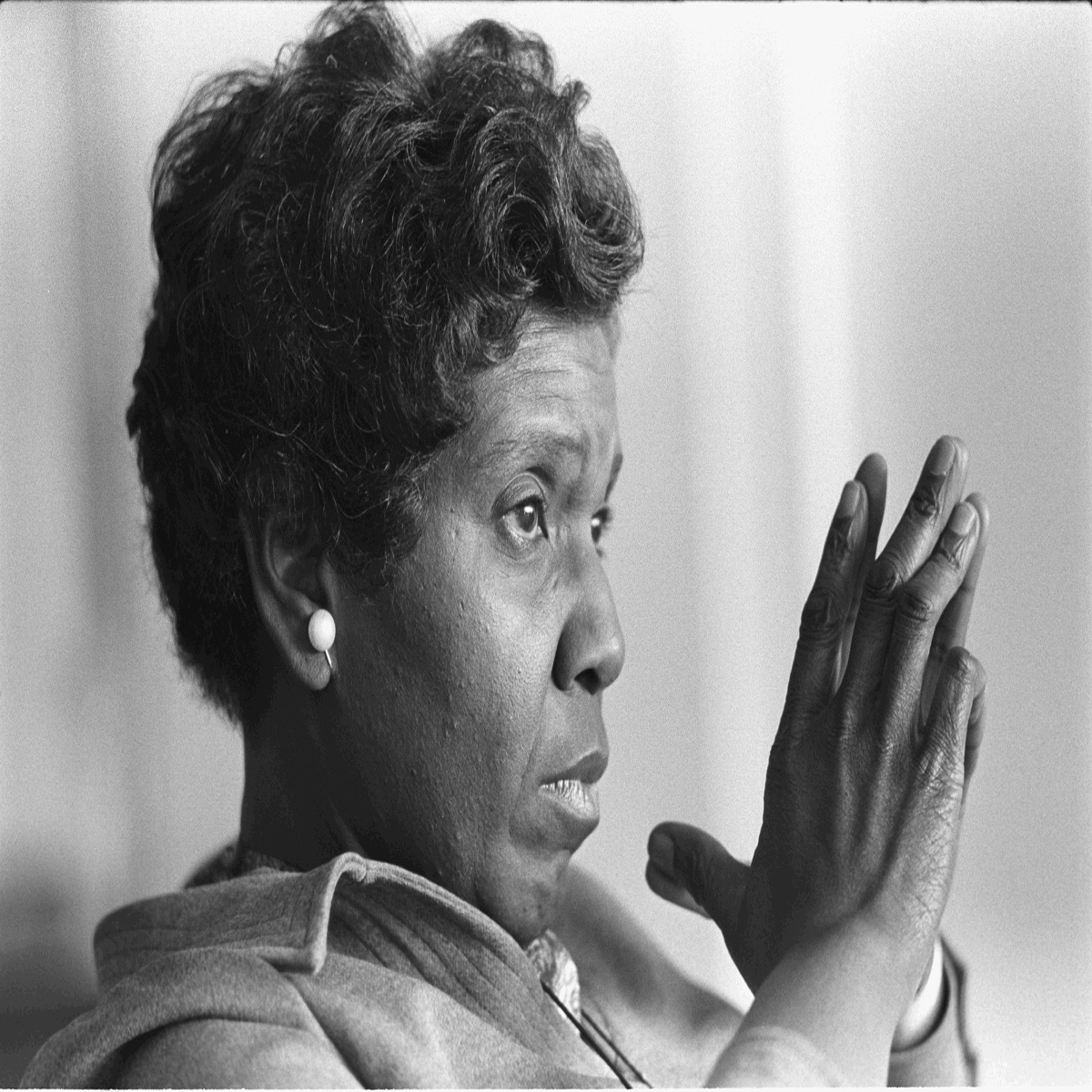

Harriet Tubman was around twelve years old, enslaved, when a fellow enslaved man attempted to run away. After being found and brought back, Harriet and a few others were instructed to help tie him up to be whipped. She refused, and when the man attempted to run again, she blocked the doorway to help him escape. An overseer threw a two-pound weight at the man but hit Harriet instead, fracturing her skull. Throughout her life, she suffered from severe headaches and narcolepsy from this incident.

A petite woman of only about five feet, Harriet was strong-willed and courageous, and as she grew older, she became determined to escape to the North. Upon learning in 1849 that she would be sold, Harriet, now in her mid-20s, decided the time was right. One night, she, along with two of her brothers, ran away. Her brothers soon turned back, and for the rest of her journey, Harriet was alone without friends. She walked at night, hid during the day, didn't know who to trust, where to eat, at times she had shelter, often she slept outside on the ground overlooked by the stars. After about ninety miles of travel, she crossed into the North to freedom.

Reflecting about making it into the North, she said, "I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person now that I was free. There was such a glory over everything. The sun came up like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in heaven."

Soon after her escape, Harriet went back into the South to help some family members to escape. After getting them North, she went back to the South to help more family members. Then she went to help others. Harriet would make many trips over the years, rescuing approximately seventy people. Of the experience, she would say, "I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can't say — I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger."

A petite woman of only about five feet, Harriet was strong-willed and courageous, and as she grew older, she became determined to escape to the North. Upon learning in 1849 that she would be sold, Harriet, now in her mid-20s, decided the time was right. One night, she, along with two of her brothers, ran away. Her brothers soon turned back, and for the rest of her journey, Harriet was alone without friends. She walked at night, hid during the day, didn't know who to trust, where to eat, at times she had shelter, often she slept outside on the ground overlooked by the stars. After about ninety miles of travel, she crossed into the North to freedom.

Reflecting about making it into the North, she said, "I looked at my hands to see if I was the same person now that I was free. There was such a glory over everything. The sun came up like gold through the trees, and over the fields, and I felt like I was in heaven."

Soon after her escape, Harriet went back into the South to help some family members to escape. After getting them North, she went back to the South to help more family members. Then she went to help others. Harriet would make many trips over the years, rescuing approximately seventy people. Of the experience, she would say, "I was the conductor of the Underground Railroad for eight years, and I can say what most conductors can't say — I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger."

Aunt Jemima existed long before Nancy Green became Aunt Jemima. Aunt Jemima was based on the Mammy Slave.

The Mammy is a common racist archetype of the older kitchen slave tasked to attend to the white family’s needs. The archetype is characterized as having ‘an implicit wisdom of her own inferiority, obedience, and submissiveness to her masters, and a hostility to black men.’ She was the female equivalent of the House Negro, who would forego having children of her own so that she could find value as a cuckold raising the children of her masters.

This archetype was adapted for comedy of the Black-faced minstrel show in 1864. The role was played by a fat white man in black face who would bumble around the stage, leaning in to her ignorance and short temper, eagerly bonking another servant with a kitchen implement. When her character would make an appearance on stage, the show would open with her theme song with the opening lyrics of "The monkey dressed in soldier clothes, Old Aunt Jemima! Oh! Oh! Oh!”

The entire concept of Aunt Jemima was a mockery of Black women. However, the only thing she could do was cook and cook well. Early Pepsi Co. would cash in on this association and created the Aunt Jemima brand, using racists caricature portraits on adds and packaging.

Nancy Green was a former enslaved African living in poverty who was discovered by a talent scout whom she cooked for, who found her to be the perfect living image of the caricature, and who could do live appearances to sell their product.

With no other financial options, Nancy Green accepted the role that mocked her very person. She surrendered who she was to assume the identity of a racist caricature and became known as Aunt Jemima in real life because it helped her become financially stable. She would then use the money she made to advocate for inequality, but knew better than to bite the hand that fed her.”

.jpg)

%20(1)%20(1).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

.webp)

.jpg)